What is migraine?

Migraine is characterised by recurrent moderate to severe headaches with a number of associated symptoms. The underlying pathophysiology is complex, involving the vasculature, central and peripheral pain signalling pathways, as well as inflammation. Both genetic and environmental factors are known to play a part in the disorder.

Internal or environmental triggers can activate a series of events that generate a migraine headache. The clinical phases of an attack are well described, but may not be experienced by everyone:

- The prodrome phase can include vague vegetative or affective symptoms as much as 24 hours before the onset of a migraine attack. These symptoms can include excessive yawning, hyperactivity, mood changes and sleepiness.

- The aura phase consists of focal neurological symptoms that last for up to one hour. Symptoms may include visual, sensory, or language disturbance as well as symptoms localising to the brainstem.

- The headache phase usually starts within an hour of resolution of the aura symptoms. The typical migraine headache usually appears with unilateral throbbing pain and associated nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to light and sound. Without treatment, the headache can last for up to 72 hours.

- The postdrome phase can last for up to 24 hours after the throbbing headache pain has resolved. Many patients experience malaise, fatigue, and transient return of the head pain in a similar location following coughing or sudden head movement. This phase is sometimes called the migraine hangover.

Migraine is broadly classified into episodic migraine and chronic migraine based on the number of days a person experiences migraine each month:

- Episodic migraine has headache attacks taking place <15 days per month

- Chronic migraine has headache attacks taking place ≥15 days per month with features of migraine on at least 8 days per month.1

How common is migraine?

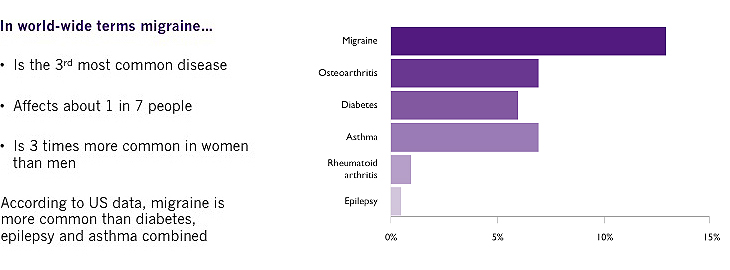

Migraine is the most prevalent disabling neurological condition and the third most common disease worldwide (after dental caries and tension-type headache) and affects up to 1 in 7 people (14–16% prevalence).2 To put this in context, migraine is more common than diabetes, epilepsy and asthma combined.3 Migraine appears to be three times more common in women than in men, probably due to hormonal changes.4

The majority of people with migraine have episodic migraine but those with chronic migraine appear to suffer most from the disorder with greater impact on daily activities, use of healthcare resources, reduced health-related quality of life and higher rates of co-morbidities.5

What is the burden of migraine to the individual and society?

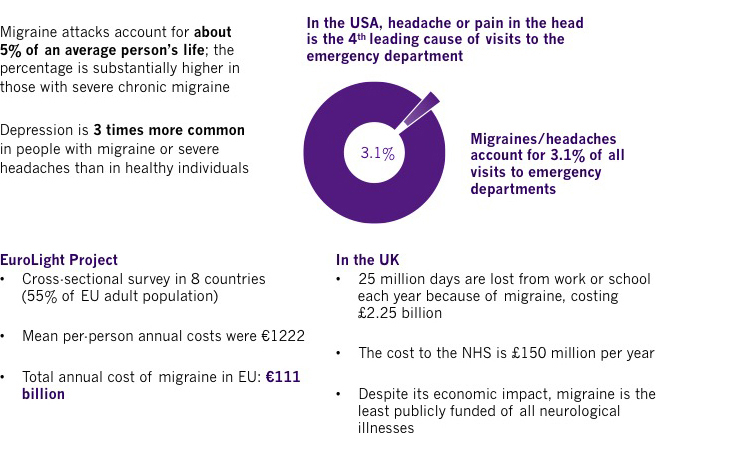

Migraine is associated with high levels of disability and financial burden on society worldwide. The disorder was listed as the seventh most disabling disease condition in the Global Burden of Disease survey 2015, affecting more than 10% of the world’s population. In the last decade (2005-2015), there has been a 15.3% increase in years lost to disability due to migraine.2,6 Severe migraine attacks are classified by the World Health Organization as among the most disabling illnesses, comparable with dementia, quadriplegia and active psychosis.7

Migraine also has a severe impact on absenteeism from work and healthcare costs. A cross-sectional survey (The EuroLight Project) across eight countries in the European Union, which included 55% of the EU adult population, showed that the mean per-person annual costs were €1222 with the total annual cost of migraine in the EU being €111 billion.8

How is migraine managed?

Not only is migraine often not diagnosed, appropriate therapeutic management is often an issue. About 50% of people with migraine treat themselves with over-the-counter medications without referral to a healthcare professional.9 The American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study found that only 56% of people with migraine had ever received a medical diagnosis. In the study, 49% used over-the-counter medications, 20% used prescription medications, and 29% used both. Only one in 8 (12%) of migraineurs indicated that they were taking a migraine preventive medication, but 17% were using medications with potential anti-migraine effects for other medical reasons.10

Drugs for acute treatment of migraine attacks include:

- Analgesics such as aspirin, paracetamol and codeine (and combinations with caffeine etc)

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, naproxen or diclofenac

- Anti-emetics including metoclopramide and domperidone

- Ergotamines

- Serotonin (5-HT1) agonists (Triptans) including sumatriptan and rizatriptan

The aims of acute treatment of migraine are to:

- Offer complete pain relief or improvement after 2 hours

- Relieve associated symptoms

- Restore normal functioning

- Prevent recurrence

- Provide consistent efficacy in 2-3 attacks

- Give sustained pain relief within 24 hours 9

Patients with frequent migraine attacks require preventive therapy for migraine. As migraine is a complicated condition, individuals vary widely in their response to therapies and therefore migraine management plans should be individualised. Non-medical approaches include counselling, exercise, stress management and relaxation techniques. Drugs classes for migraine prevention include:

- Beta-blockers, such as propranolol and metoprolol

- Anticonvulsants including topiramate and sodium valproate

- Calcium channel blockers, such as flunarizine

- Angiotensin II blockers, such as candesartan

- Antidepressants, such as amitriptyline and nortriptyline

These drugs, on average, reduce migraine frequency by 50% in about 40–45% of patients. However, compliance and adherence is poor because of their many adverse events.11

The aims of preventive treatment of migraine are to:

- Reduce the frequency and severity of attacks by ≥50%

- Reduce the duration of attacks

- Improve responsiveness to acute therapy

- Prevent medication-overuse headache

- Improve function and reduce disability9

What are the unmet needs in migraine prevention?

Both acute and preventive therapies can be ineffective or poorly tolerated and some have significant contraindications. For example, triptans, despite having only weak vasoconstrictor properties in humans, are contraindicated in patients with severe vascular conditions such as angina or ischaemic stroke, and in people with several untreated vascular risk factors. This significantly restricts treatment choice for these patients. Therefore, new drugs are needed to treat migraine attacks in patients in whom triptans are not effective, are initially effective but symptoms recur, are poorly tolerated, or are contraindicated.

Despite many management guidelines being published by expert groups and policy makers (e.g. American Headache Society, NICE, SIGN, Canadian Headache Society, British Association for the Study of Headache, etc; refer to http://www.cgrpforum.org/resources/links/) there is discordance between them in some areas including classification and risk-benefit profile for treatment options. There is a clear need for consistent guidelines endorsed by all interested parties.

Patients report that lack of efficacy and high levels of side effects are the key reasons for them discontinuing preventive migraine medication.12 These factors mean that side-effects adherence with migraine preventive therapy is generally low (<30% at 6 months, <20% at 1 year).13

In summary, the unmet needs for migraine prevention include:

- Underdiagnosis and undertreatment

- Lack of concordance between guidelines

- Efficacy and tolerability

- Poor long-term adherence

- Co-morbidities that restrict treatment choice

References

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013;33:629-808.

- Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Birbeck GL. Migraine: the seventh disabler. The Journal of Headache and Pain 2013;14(1):1.

- Headache Disorders – not respected, not resourced. All-Party Parliamentary Group on Primary Headache Disorders. 2010.

- World Health Organisation. Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2011. Available at : http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/atlas_headache_disorders/en/

- Dodick DW, Loder EW, Manack Adams A, et al. Assessing barriers to chronic migraine consultation, diagnosis and treatment: results from the chronic migraine epidemiology and outcomes (CaMEO) study. Headache 2016;56:821-834.

- GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1545–1602.

- Shapiro RE and Goadsby PJ. The long drought: the dearth of public funding for headache research. Cephalalgia 2007;27:991-994.

- Linde M, Gustavsson A, Stovner LJ et al. The cost of headache disorders in Europe: the Eurolight Project. Eur J Neurol 2012;19:703-711.

- Giamberardino MA, Martelletti P. Emerging drugs for migraine treatment. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2015;20:137-147.

- Diamond S, Bigal ME, Silberstein S, et al. Patterns of diagnosis and acute and preventive treatment for migraine in the United States: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study. Headache 2007;47:355-363.

- Diener H-C, Charles A, Goadsby PJ, Holle D. New therapeutic approaches for the prevention and treatment of migraine. Lancet Neurology 2015;14:1010-1022.

- Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, et al. Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation of prophylactic medications for episodic migraine and chronic migraine: results from the second international burden of migraine study (IBMS-II). Headache 2013;53:644-655.

- Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon S et al. Adherence to oral migraine-preventive medications among patients with chronic migraine. Cephalalgia 2015;35:478-488.